These days, it seems, racial injustice protests and college sports go hand and hand. In the aftermath of George Floyd’s death, even the Razorback football head coach — Sam Pittman — joined a Black Lives Matter rally to show his support for the African-American community that has struggled with institutional, systemic constraints dating back centuries.

Such a show of support was unthinkable even just a couple of years ago.

The legacy of unofficial black Razorbacks dates back to the 1930s in Fayetteville, but when it comes to official black Razorbacks, that didn’t begin until the mid to late 1960s with the likes of Darrell Brown and Hiram McBeth.

By 1968, there still had not been a scholarship black Razorback in football (nor would there be one until 1970 with Jon Richardson.)

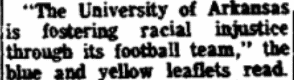

But, even in the fall fo 1968, a few brave UA students pushed to see integration of their all-white football team. The below article, which ran in the Arkansas Gazette on September 26, 1968, is the first known instance of UA students protesting social injustice in the context of Razorback sports:

The football player mentioned at the end of the story is the late, great Darrell Brown, who showed tremendous courage by sustaining bodily harm to break down barriers in 1965.

Among the first scholarship Razorback basketball players were two Fort Smith products, Almer Lee and Jerry Jennings (who later played football).

Before them, however, were Thomas Johnson (who attended Menifee) and Fayetteville native Louis Bryant, the first black Razorback basketball player whose status in history has been all but forgotten.

*In the 21st century, of course, the term “Negro” is very offensive. However, in the 1960s and before the advent of the phrase “African-American” and the prevalence of “black person,” it was widely considered a socially acceptable term.

***

Want to learn more about the heritage of black Razorbacks and African Americans at the UA? Make sure to check out “Remembrances in Black: Personal Perspective of African American Experience at the University of Arkansas 1940s-2000s” and “African-American Athletes in Arkansas: Muhammad Ali’s Tour, Black Razorbacks and Other Forgotten Stories.”

***

Why 40 Black University of Arkansas Students Barricaded the UA’s Journalism Building

The story of the first organized form of protest by University of Arkansas African-American students.

In my last post, I discussed how the first student strike in UA history came as a result of strong disagreement with the standards of the student newspaper. Nearly 60 years after that “X-ray” strike, another student uprising followed conflict with their newspaper’s editors. This time around, about 40 black students blockaded the journalism building as part of a protest that gave rise to a UA organization called Black Americans for Democracy (now called the Black Students Association).

The assassination of Martin Luther King in the spring of 1968 was a major catalyst in black UA students banding together to address an on-campus situation which had become “unbearable,” according to Mordean Taylor Moore, a UA graduate student in his 1972 dissertation “Black Student Unrest at the University of Arkansas: A Case Study.”

Moore wrote: “The [UA] students reacted to the assassination of Dr. King holding memorial services and marching through the campus and downtown. Both black and white students as well as faculty members participated in these events. The expenses for three black students to attend the funeral of Dr. King In Atlanta were paid by contributions from local citizens, and before leaving Fayetteville, the students were given a letter of condolence from the University president to deliver to Mrs. King. In addition to these activities, the official day of mourning was recognized by the University with dismissal of classes.

Following these events, a white student wrote to the school newspaper complaining of all the publicity that was given to the death of Dr. King. This letter appeared In the editorial section of the school paper. However, when a black student* wrote a letter to the editor in response, the school paper failed to print it.

This act triggered the first overt form of protest by University of Arkansas black students.

The black students reacted by barricading the journalism building on campus. Reportedly, about forty black students blocked the building for several hours preventing the publication of the school paper as well as other printing done in the building. This

protest resulted into an open meeting of the board of publication and administration with, the black students.

The black students openly attacked the school newspaper for not representing the whole student body and called for an end of Its publication unless change was made in its discriminatory editorial policies. The black students stated that they felt they had to protest to such a manner because they had exhausted all official channels; a letter had been written to the editor of the school paper requesting that the list of their grievances** be printed, they had spoken to the Dean of Students concerning their dissatisfaction with their situation on campus and had requested a meeting with the board of publication. These attempts through the proper channels were to no avail.

The following fall semester, the black student organization worked hard at improving the situation of black students on campus. They held several black-white conferences on race relations on campus wherein they stated that they felt isolated on campus and [an integral part] of the university.”

* John Rowe

** According to UA archivist Amy Allen, “BAD had a list of thirteen demands, including ending discrimination in room assignments, sororities, fraternities, and athletics; enactment of policies for reporting unfair classroom treatment to a faculty-student committee; creation of a black history course; recruitment of black faculty, administrators, and staff; and banning the playing of the song ‘Dixie’ and the use of black face grease paint at official university functions.”

***BAD formed its own newspaper, initially called The Bad Times. You can read past copies in the UA’s digital archives here.

Why does it always seem about race ?? Why can’t all races work together on an even basis. I see a lot of black people wanting power over white people. That is not a fair thing to allow . We don’t have white entertainment like BET nor do we have white colleges or a white football league all of which black people do. That’s not showing fairness and one day soon that is gonna cause an uprising of white people as well as black peoples then what do you have ?? Come on I thought this university was smarter than to allow such one sided privileges . I’m tired of hearing white privilege because I’ve never experienced it myself . Your going down a road and our country that will eventually cause a nationwide race war .

Why does it always seem about race ?? Why can’t all races work together on an even basis. I see a lot of black people wanting power over white people. That is not a fair thing to allow . We don’t have white entertainment like BET nor do we have white colleges or a white football league all of which black people do. That’s not showing fairness and one day soon that is gonna cause an uprising of white people as well as black peoples then what do you have ?? Come on I thought this university was smarter than to allow such one sided privileges . I’m tired of hearing white privilege because I’ve never experienced it myself . Your going down a road and our country that will eventually cause a nationwide race war .

Hey Greg, I appreciate you sharing your viewpoint. I know a lot of Arkansans — and Americans in general — share your views, and I embrace the opportunity to talk about race.

Race is a tricky subject, in my opinion, for many reasons. One of them is that the past still influences the present, no matter how much we wish it didn’t. The effects of centuries of slavery and then decades of Jim Crow law were not wiped away — they still affect us to this day.

In sports terms, think about how the Arkansas Activities Association is a record-keeping body that extends back to the 1910s. All the schools and players listed from the 1910s to the 1960s are white. It turns out that no all-black schools are listed in that record book until integration in the 1960s.

All the all-black school records were lost or destroyed while the all-white school records were preserved. So the latter become part of our collective “official” history, while the former is forgotten. That’s not the fault of anybody alive today. It’s just a matter of fact reflection of how segregation laws decades ago affect what we perceive of “true” history today.

In truth, large parts of our history as Americans (no matter our race) are lost, destroyed and forgotten b/c of institutional customs long ago. This goes way beyond just race. It’s also socioeconomic and gender related. So it happens to poor white Americans, and especially to poor white American women, too.

I don’t think this is about blacks having power over whites, or whites having power over blacks. It’s about honoring the truth of what really happened, for all Americans, instead of seeing only a part of the truth.

I go more into it here: http://www.bestofarkansassports.com/wally-hall-the-arkansas-activities-association-the-loss-of-a-states-athletic-heritage/