Remembering the River Bucks, a black baseball team out of Cross County, Arkansas.

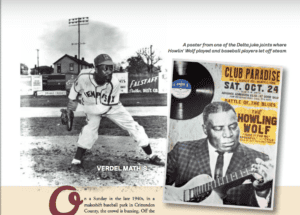

On a Sunday in the late 1940s, in a makeshift baseball park in Crittenden County, the crowd is buzzing. Off the field, a young, thin bluesman named B.B. King ascends a wooden platform wearing a blue suit. As his drummer kicks it up, the young prodigy begins wailing on his guitar. The men shooting dice under a tree’s shade stop for a bit to enjoy the show.

On the field, Isaiah “Lefty” Harris is creating a heat all his own. The ace pitcher’s throwing cutters and fastballs that leave batters twisting in the air before they smash into the glove of his catcher, Johnny Cole. Hundreds of black fans jammed into the wooden stands roar. The River Bucks are back.

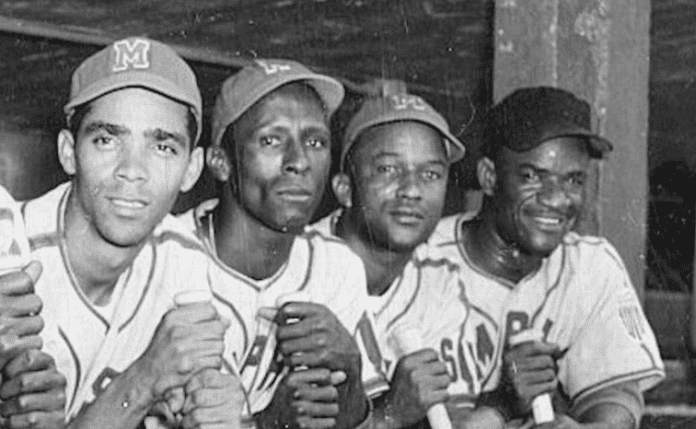

The River Bucks were one of many black baseball teams which played semi-professional baseball throughout the South in the early to mid 20th century. Almost every Arkansas community had either a black or white baseball team. Many had both.

In the more than three decades the team existed, it played communities like Earle, Forrest City, Carlisle, Marked Tree, Crawfordsville, Blackfish Lake and professional teams like the Memphis Blues (of the Negro Southern League) and Memphis’ Brown Derby Bombers.

Many black communities in the Delta had juke joints with ballfields to host Sunday black baseball games.

The first River Bucks team emerged by the 1930s as one of a few “plantation teams” in the Delta, says historian Faye Futch, granddaughter of original River Buck U.L. Hinton. They first played on the Smith family-owned pasture land of Birdeye. The first River Bucks also came from Coldwater, a community near the St. Francis River which inspired the team name, according to Futch.

U.L. Hinton and the first team’s foes included the powerhouse Claybrook Tigers, based in southern Crittenden County. The Tigers won two Negro Southern League titles before folding in 1937.

James “Jack” Wynn, a native of the Parkin area, is one of the few men alive who remembers the second-generation River Bucks of the late 1940s and early 1950s. Wynn had a few relatives on the team, including cousin Euren Hinton (U.L. Hinton’s son) and uncle Johnny Cole.

Wynn attended many of their games in his early teens. He doesn’t know of any River Buck players from this time alive today, but still clearly remembers players like his cousin, uncle, and the three Harris brothers — Isaiah, James and Letroy — who were raised along with three other brothers by their father after their mother died.

These River Bucks came from Parkin and Cherry Valley as well as Birdeye and Coldwater. Most of the men, in their 20s, were World War II veterans looking to pass time.

“There wasn’t anything else to do,” Wynn says. “No restaurants, zoos, playgrounds.”

There were, of course, juke joints on the east Arkansas section of the “Chitlin’ Circuit,” including many in the the “Bottoms” community in Parkin. B.B. King and Chester “Howlin’ Wolf ” Burnett frequently played blues in these joints. (One especially hopping joint was Babe Mason’s in Twist, just across the St. Francis River. That’s where B.B. King met Fannie Robinson of Coldwater. The two dated and had a son named Leonard King, says Futch.)

Still, outdoor, day-time recreation options were in short supply.

At some point in the late 1940s the River Bucks also began playing in Julius, just southeast of Crawfordsville. They shared that turf with the Julius Greyhounds, a team made up of many Memphis players, Wynn recalls. The owner of the field was a well-to-do white man — Futch recalls him as “Mr. Julius” — who lived in a plantation home near the field and a store. He owned the surrounding crop fields and got at least half the gate brought in by games, as well as a sizable cut of concession sales.

Life was harder then. While many of the Memphis black baseball players worked in factories, the River Bucks worked as sharecroppers of cotton and soybeans. Some of them sharecropped for the ballpark’s owner, recalls Wynn, now 82 years old.

Weekend afternoons were a time to let off some steam. In the early years “Howlin’ Wolf”s brother in-law, Sonny Boy Williamson II, performed before and after games in Julius and Crawfordsville. Then B.B. King took his spot. There was gambling, food and drinks aplenty: fried fish, hot dogs, BBQ, Goldcrest 51 beer, corn whiskey, RC Cola and Double Cola.

By the 1960s, admission to River Buck games in Birdeye was free. Bootleggers sponsored many of the teams the River Bucks played and got paid through off-the-books revenue from gambling and concessions, according to Lafonza “Lee” Barton, who played for the River Bucks in the early 1960s.

The men who owned the fields (and knew local law enforcement) understood what was going on, but they didn’t mind.

“As long as we got up on Monday morning and went to work on that farm, the police wouldn’t come,” Barton says. Crowds for the second-generation River Bucks could reach 400 to 500 people, with 60 or 70 of them driving to Julius from Memphis, but Jack Wynn doesn’t recall things getting out of hand.

“Every once in a while someone would get mad, maybe throw a beer bottle, but no guns were fired or anything like that. I can’t remember anybody getting hurt.”

Isaiah Harris (via arkbaseball.com)

For some players, the good times never ended. Isaiah Harris, for instance, started playing for the Negro Leagues’ Memphis Red Sox in 1949. He starred there, too, getting selected to four East-West all-star classics and once pitching two no-hitters in the span of five days against the Kansas City Monarchs. Wynn recalls at some point the Chicago White Sox drafted him, but Harris enjoyed Memphis partying too much to give the majors a shot.

“He had fallen in love with Beale Street and didn’t want to go.”

[yikes-mailchimp form=”1″ title=”1″ description=”1″]

The above is Part 1 of my black baseball story which originally published in the Fall 2018 issue of Delta Crossroads . To read Part 2, click here.

-Evin Demirel

Evin, this is an excellent article. I wanted everyone to know about the River Bucks, and now they do. Thank you so much and the community of Birdeye and Parkin thank you.

Thank you, Faye! Feel free to give me a heads up on other unreported stories, too.