It’s March, which means basketball fever is spreading through Arkansas. Interest in the high school state tournament is extra high this year as the state enjoys a high school basketball golden age thanks to headliners like junior KeVaughn Allen and sophomore Malik Monk. Both highly recruited shooting guards are accomplished beyond their years. Last year, Allen helped lead North Little Rock to a state title as a sophomore and picked up Finals MVP along the way. Monk, ranked by some outlets as the best shooting guard in the nation in his class, may one-up him. Despite two late season losses, Monk has helped turn Bentonville into a powerhouse for the first time in a long time while racking up obscene box scores. (Who else hits 11 of 12 three-pointers, as Monk did in one January game?)

Allen and Monk, who both stand around 6-3, aren’t the first sophomore wing players to dominate the local high school scene. In the early 1970s, another great high school golden age was tipping off and Little Rock native Dexter Reed was in the thick of it. The 6-2 guard went on one of the most devastating tourney tears of any era to lead Little Rock Parkview to its first state title.

In 1971, Parkview had only existed for three years. All the dynastic names affiliated with the school now — Ripley, Flanigan, Fisher — were still far off in the future. These ‘71 Patriots finished their regular season with a 15-12 record, but caught fire in the state tournament at Barton Coliseum, knocking off Jacksonville, McClellan, Jonesboro and finally, Helena. Through those four games, Reed averaged 27 points including 43 to secure the Class AAA title, then the state’s second largest. Ron Brewer, who regularly played pickup ball with Reed in the 1970s, said his friend was among the best scorers in state history: “He was like a choreographer out there, just dancing and weaving and getting the defense all discombobulated. And when it’s all said and done, he just destroyed you. He destroyed you by himself.”

Reed was a different kind of player from Monk and Allen but effective in his own way. The new schoolers are both extremely explosive athletes with deep three-point range. Reed didn’t play above the rim, and he didn’t see much reason to shoot 21-footers in his three point shot-less era. “I wasn’t the best of shooters,” he says. “I was more of a scorer. I could get by people, you know — I tried to be like Earl the Pearl.”

Reed won another title as a junior and by his senior year was a second-team Parade All-American who had hundreds of scholarship offers. The University of Arkansas was an early favorite. Reed had grown up a Razorback fan, and many in his inner circle wanted to see him play for coach Lanny Van Eman. Among those was local coach Houston Nutt, Sr., who had taught him the game’s fundamentals. “He had a lot of influence on me,” says Reed, who as a boy had sold popcorn at War Memorial Stadium with Houston Nutt, Jr.

Memphis State University, fresh off a national championship appearance, also entered the recruiting picture. Reed’s parents liked the fact that its campus was more than an hour closer to their home than Fayetteville. Other factors tipped the scales Memphis’ way. For starters, the Tigers played in an arena that didn’t make Reed uncomfortable. One area of the Hogs’ Barnhill Fieldhouse where the football team worked out was covered in sawdust. “I had sinus problems, and I’d be coughing there during summer basketball camps,” he says. Moreover, Reed’s older brother already attended the UA but had had trouble socially acclimating. Reed’s brother told him to strongly consider a larger city as Fayetteville was then a small town and there “wasn’t but a handful of black kids.”

Dexter Reed chose Memphis State and as a freshman immediately made a splash, racking up more than 500 points and leading the Tigers to a 19-11 finish. A serious injury to his knee ligaments the following season diminished his quickness, but he bounced back to average 18.8 points a game as a senior and landed on two All-America teams.

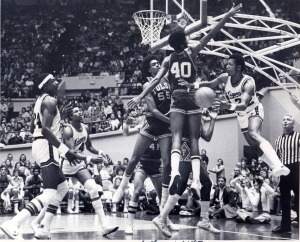

One highlight his last year was a return to Little Rock to play a surging Hogs program under new coach Eddie Sutton. As Sutton’s first great Hogs team, that 1976–77 bunch only lost one regular season game. On Dec. 30, 1976, a then record crowd jammed into Barton Coliseum to watch Reed, the greatest scorer Little Rock had ever produced, square off against Hog stars like Brewer, a junior, and sophomores Sidney Moncrief and Marvin Delph. They were all friends and ribbed each other in advance of Reed’s only college game in his hometown. Brewer recalls, “Me, Sidney and Marvin kept saying ‘You can come back all you want, but you ain’t gonna win this one.’ And he single handily kept them in the ballgame.”

Arkansas led for most of it, with Reed guarding Moncrief and then Brewer. But Reed and the bigger Tigers finished strong, with Reed hitting free throws down the stretch to clinch a 69-62 win. “I didn’t really think it was that big to my teammates, but after it was over, they all came over jumping on me,” Reed says. As he left the arena, he recalled seeing some of the same people in the crowd who had watched him burst onto the stage seven years earlier as a Parkview sophomore. “It was like a time warp,” he says.

Fast forward to the present, and Reed still lives in Memphis, where he runs sign and flower shops and hosts a sports radio show every Saturday morning. His parents have passed, so he doesn’t make it back to Little Rock much anymore. But he still follows the Razorbacks, and he’s heard from friends and Memphis coaches about some of the state’s great high school guards like KeVaughn Allen. Reed is glad to know the tradition he helped nourish is in good hands. He concludes, “My heart has always been with Arkansas.”

An earlier version of this story was originally published in this month’s issue of Celebrate Arkansas.