The Little Rock School District’s new superintendent lays out a vision in which dollars could flow to technology, pre-K and “wrap-around services” instead of football.

On Tuesday, new LRSD superintendent Michael Poore expanded on his plans to help turn around the long-struggling district. He covered a wide gamut of topics, from going to the ER this past weekend to pre-K education and “wraparound services” for poor students.

He stressed plans to build partnerships between middle school and high school students and local business leaders, leading to mentorship opportunities and project-based learning that would involve more after-school, weekend and summer learning sessions. He advocated for tech lab-like settings, likely in a business, near each of the LRSD high schools where this learning could take place.

Not once, though, did he mention athletics.

What role do sports — specifically football — play in the LRSD’s future if Poore’s vision becomes reality? Football is expensive and many of Poore’s ideas for expanding school services while expanding technical infrastructure will involve a lot of money. It’s probable insurance premiums for high school football will rise in the coming years as more data is uncovered linking “micro-concussions” and long-term cognitive defects. Meanwhile, starting after the 2017-18, the LRSD will lose $37 million in supplemental aid stemming from desegregation case settlement.

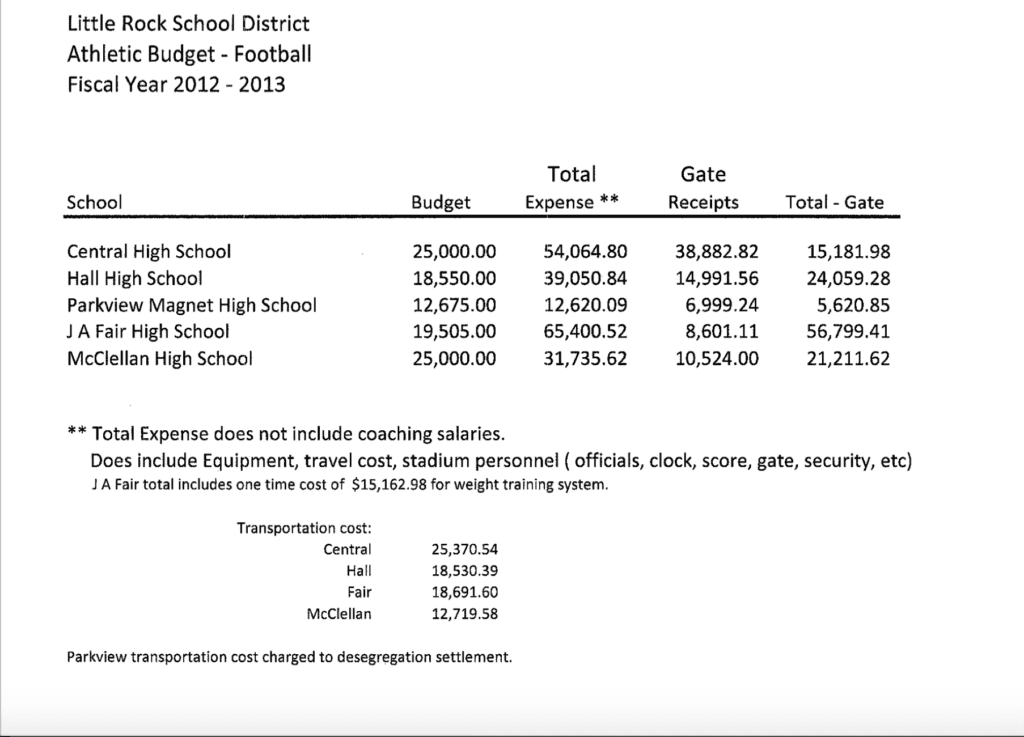

For years, LRSD football has leaned on that money to pay for the buses that transport students to and from practice and games.

In 2013, busing for LRSD football players alone cost $75,000. When encompassing all sports, at all schools, and including drill team and cheerleaders, the cost was $350,000 in all. That cost has surely risen.

What will happen to LRSD students who need busing for sports events when the desegregation money runs dry?* Perhaps the money will come from another budget(s) within the district. Such an expenditure may spark a domino effect ultimately leaving less money available to invest in the programs and technology tools that Michael Poore is now espousing.

When discussing his ideas for project-based learning opportunities with local companies, Poore noted the success he had experienced with students at his previous superintendent job in Bentonville. This town (my current residence) does not lack for local civic pride and, by extension, strong support of its public schools. For proof, simply walk through the Tigers’ swank football stadium and basketball arena. The scoreboards and walls around those facilities are swamped with advertisements from local companies, many are Walmart or its vendors. Moreover, Bentonville High boosters (many of whom work for Walmart or its vendors) pay good money to buy season seats to attend football and basketball games.

But Little Rock, my native city and residence through 2014, presents a different story.

It has five public five schools, not one or two as the NWA cities do. Little Rock Central High athletics still gets plenty of corporate support and donations from alumni, but private fundraising is more of a struggle for the others, especially McClellan, Hall and Fair.

Moreover, that spirit of civic boosterism we see in each of the NWA cities is dispersed even more in central Arkansas because of the emergence of major private schools in the area like Pulaski Academy, LR Christian, CAC and Episcopal Collegiate School in recent decades. They now take some of the private booster funds that in the 1970s and 1980s would have gone to the public schools.

Finally, further darkening the horizon, we see the current growth of public charter schools like eStem and Lisa Academy. These schools don’t even play football, so they don’t present a danger to siphoning off top players and coaches like the football-playing private schools do. But they are aggressively proliferating in the area and it appears that their growth curve may be on the upswing for two reasons:

a) the Walton Family Foundation recently announced it will pour $250 million into charter school infrastructure in 17 cities across the U.S. including Little Rock, in addition to the $1 billion the WFF previously announced it would spend over the next five years to help new and existing charters.

b) The Arkansas state government appears open to laws allowing more and more current LRSD students to use waivers for transfer into a charter school of their families’ choosing. Public school revenue is tied to enrollment figures, so each time a student leaves the district, the amount of money available for future non-academic expenditures would theoretically decrease. There may not be enough money to fund all of Poore’s ideas and keeping up with the Joneses in all team sports.

Could these forces lead to a time years from now when LRSD football, at least at some schools, finds itself on the budgetary chopping block? I don’t foresee this happening any time soon at a place like my alma mater LR Central, but it will be interesting to see if a growing cohort of LRSD supporters push for this to happen at select schools.

Little Rock Fair High, for instance, has a dismal football program. Why not figure out a way to cancel the program, but in its stead give the students who would have joined the team options to

a) learn marketable computer skills to create their own football or eSports video games at a local “tech” center

b) Play for a nearby public high school like McClellan or the new high school in southwest Little Rock currently in the tentative planning stages

In Arkansas, cutting high school football from some schools within a district but allowing it stay at others is rare if not unprecedented. It already happens at the college level — see football-free UALR in the Sun Belt Conference — but there would be pushback to brainstorming a legal reconfiguration to make this work at the high school level.

This political climate is as good any to figure out a way, though. Earlier this year, Arkansas lawmakers passed legislation allowing traditional school districts to apply for the same waivers of rules and laws that are granted to the open-enrollment charter schools that enroll students who live within the boundaries of the traditional district, the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette’s Cynthia Howell noted.

She added: “Open-enrollment charter school waivers typically include waivers of teacher and administrative licensure requirements. Other typical waivers are for time requirements for a course or for the length of the school year or school day. Waivers also are sought to allow the combination of courses, or for alternative means of providing health, counseling and library media services.”

The rah-rah selling point for prep football is that it provides students physical exercise along with lessons on teamwork, competition, discipline. Whether intended or not, though, the LRSD’s new head just outlined alternative means to those ends better suited to the 21st century.

*Admittedly, these answers should be only a few phone calls away. I haven’t yet made those calls. Fill me in with what you know, dear reader.