“I read that Martin Luther King said, ‘A man who won’t die for something is not fit to live.’ I was like, dang. You know, I would die for boxing. I know that’s dumb. You’ll say, ‘You got your kids — your family.’ I know. But still, you died fighting. Jermain Taylor is a boxer.” – Jermain Taylor, 2013

Through much of the last week, thousands of central Arkansans have thronged the streets of downtown Little Rock to protest social injustices and police brutality.

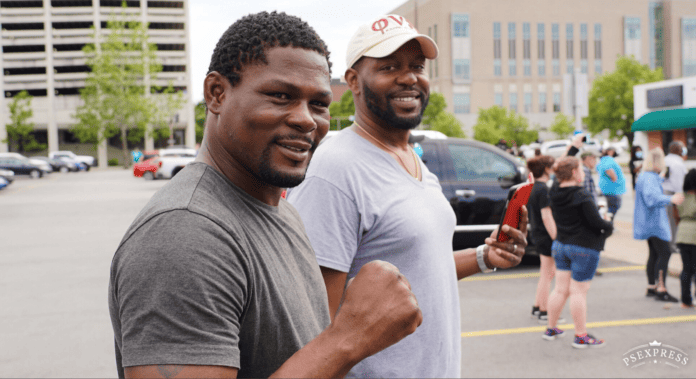

Among the many was a familiar face: Little Rock native Jermain Taylor, the most talented boxer Arkansas has ever produced.

Good to see this guy smiling. His life has been a rollercoaster ride…. the highest of highs and the lowest of lows. Jermain is proud to be the father of a State wrestling champ. pic.twitter.com/cQye07a1g4

— Steve Sullivan (@sully7777) June 2, 2020

In the midst of all the chanting, it’s possible Taylor let himself go back in time, if only for a moment. To the same place, but in 2005, when downtown Little Rock was all but shut down for a massive parade held in his honor.

He’d just defeated Bernard Hopkins in a 12-round slog to become the unified middleweight champion of the world, the culmination of a boxing journey he’d started as a 13-year old.

Practically every step on his way up the mountain, from those early days under the tutelage of Ray Rogers, to his bronze medaling at the 2000 Olympics, he’d bled Razorback red and touted state pride.

At the end of every fight, when he did an interview, Taylor said: “I love you, Arkansas.”

***

***

And my, how Arkansas loved him back. In the 2000s, only Darren McFadden rivaled him as the state’s most popular athlete.

Jermain Taylor hung on to his belt until 2007, when he lost it to Kelly Pavlik (who, like Taylor, has also gotten into trouble with the law).

Yet even during his height, it seemed, he had already lost some of the abilities of his younger years. Some of that was due to his inability to click with his second trainer, Emanuel Steward. Steward had a prestigious career, advising or training the likes of Oscar De La Hoya, Lennox Lewis, Evander Holyfield and Tyson Fury, but his direct style didn’t bring out the best in Taylor.

But there was a more serious issue at play. Jermain Taylor “never treated boxing like a profession,” KATV sportscaster Steve Sullivan wrote in 2015. “He was and is still a prize fighter. Between fights it was common for Jermain to put on up to 20 pounds and then work like heck 6 or 7 weeks prior to the fight to shed those pounds.”

“Prize fighters are not a good bet for long term success in or out of the ring.”

***

***

In 2014, although he regained a middleweight championship belt, Taylor’s career began to fall apart. With his physical skills on the decline, his self-control and judgment abilities seemed to nosedive.

From 2014 to 2018, he flashed horrifying bouts of anger multiple times, ran around toting guns, hit and threatened folks and was arrested multiple times:

*On August 26, 2014, Taylor was arrested for allegedly shooting a cousin

*On January 19, 2015, he was arrested in Little Rock on assault charges.

*On December 1, 2015, Taylor pleaded guilty in three cases but agreed to conditions that allow him to continue boxing.

*On May 20, 2016, Taylor was given six-year suspended sentences on eight of nine pending charges, and a one-year suspended sentence on the ninth, along with 120 hours of community service, a $2,000 fine, and mandatory drug testing.

*On July 18, 2017, Taylor was arrested and charged with charged with misdemeanor third-degree battery, felony terroristic threatening, and misdemeanor interference with emergency communication as the result of a domestic disturbance.

*On August 29, 2018, he was arrested again for domestic battery.

Since 2018, however, Jermain Taylor has pretty much stayed out of the news. He’s still active on Instagram, posting pictures of the family he is proud of:

Indeed, Jermain’s son, Jermain Taylor, Jr., is a champion in his own right. Representing Little Rock Central High, junior won the state’s 6A wresting title.

***

There is some irony that Taylor attended a protest against police brutality.

It’s not just because the police have played a vital role in protecting some of the reported victims (and potential victims) of Taylor’s rage.

It goes deeper than that.

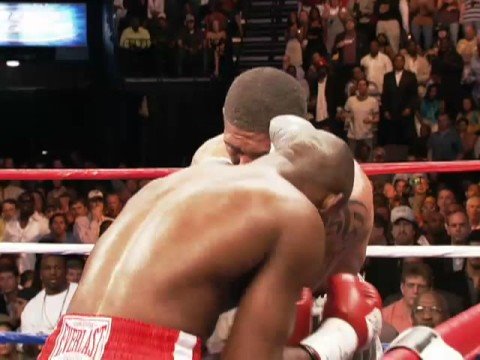

Given his erratic, violent behavior over the last half decade, it’s clear Taylor is showing signs of brain damage — suffering the effects of more than two decades worth of pounding to the head, punctuated by three vicious KOs in the span of five matches at the hands of Pavlik, Carl Froch and Arthur Abraham.

The last one, against Abraham in Berlin, was especially disturbing. He suffered a brain bleed, the primary cause of death in the sport.

“Returning to Little Rock was a reality check,” Carmen Thompson wrote for ESPN.com. “Where were the parades and well-wishers now that he desperately needed a pick-me-up? Where were his boys, the entourage he’d taken to Berlin and plied with gifts? His cellphone was disturbingly silent. There was nothing to distract him from the pounding, debilitating headaches that even a steady dose of painkillers could barely blot out.”

Already, at that point in 2011, it was clear Taylor should have called it quits. “If you stay too long in baseball, your lifetime batting average goes down, but in boxing you may be eating out of a straw,” his former promoter Lou DiBella said.

Taylor got testing done at the Mayo Clinic and Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health to show there was no signs of the brain bleed. Still, at that point, there probably would have not been conclusive signs of the CTE that is especially insidious among boxers and football players as it accumulates over years from micro traumas, instead of from a singular event.

So Jermain Taylor kept fighting. After a brief break, he would keep fighting until the International Boxing Federation formally stripped him of his middleweight world title in February 2015.

***

A bizarre, expletive-laced “apology” video of Taylor from 2015

***

Yes, some of the blame is on Taylor for deciding to keep on going. But shouldn’t blame also fall at the feet of a system that allows re-licensing of fighters with a history of brain bleeds, as the Nevada State Athletic Commission did in Taylor’s case?

“The licensing of fighters who have no business stepping into a ring and lax communication is but one way fighters are failed, and but one crack in a nearly-broken system,” Patrick Connor points out in The Guardian.

Yes, we want to believe that a boxer would be able to call it quits for the love of his family. But when that boxer and that familly has been reliant on the millions made through prizefighting, it’s very hard to turn down the prospect of even a few hundred thousands more.

“Quite simply, there is no incentive for a fighter to stop fighting,” Connor writes. “There is no pension, no support system or institution stepping in when a fighter who knows no other profession and has no way of making money needs help. There is no incentive for promoters to work together, or for non-participants to not excise their pound of flesh.”

Taylor needs more than a substance-abuse rehab program. That doesn’t address the core issues in his case. He needs an intensive program or facility to help treat people who are suffering mental problems on behalf of brain damage.

Boxing means brutality, and there’s no protesting that fact. The sport will go on. But we need better regulations to make sure Arkansas’ next great fighter steps out of the ring way before Taylor did — and gets the right kind of help afterward.

Nobody, after all, expects boxers to train themselves to become the best fighters they can be.

Nobody should expect our broken warriors to fix themselves, either.

***

“Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.” – Martin Luther King

***

For more perspective from Arkansas journalists who covered Taylor for years, watch this:

***

For our most recent post, go here: