At all levels, from high school to the pros, African Americans served white athletic teams in the Jim Crow era. Many received nicknames which verged on honorifics such as “Doc” and “Senator.” Others got more disparaging nicknames. At the University of Tennessee, James Forgey was known as “Dummy.” And then there’s Jack Shelton of Rice University.

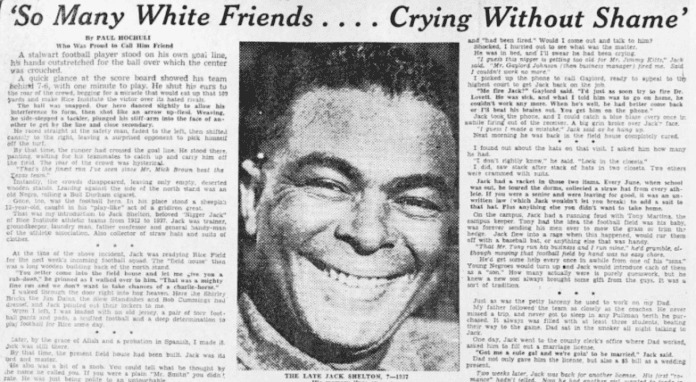

Below is the wince-inducing opening of a student newspaper article about Shelton circa October 27, 1933:

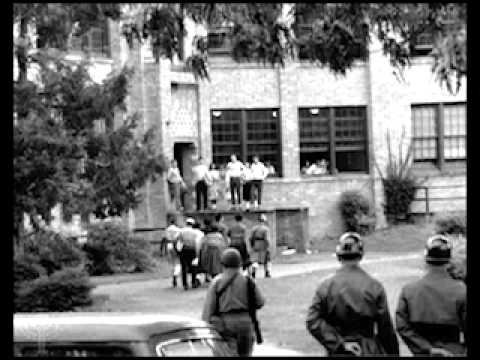

Jack Shelton was one of a select number of blacks across the South who were allowed access to typically white-only spaces, so long as they played a servile role. Such limited acceptance is at the heart of the system of paternalism. So at my alma mater Little Rock Central High, trainer Riley Johns was beloved, so long as he served whites and did not try to stand on equal footing with them. When an attempt along those lines actually happened in 1957, it’s probable that some of same folks standing in front of Central High trying to bar Elizabeth Eckford were among the 4,000 folks attending Johns’ funeral just seven years prior.

At Rice, Shelton was depicted as beloved by whites as Riley Johns had been at Central. The authenticity and depth of this affection would have varied by person. Regardless, a key reason many whites “loved” Shelton was he never challenged their power and status. All the glowing, unctuous newspaper accounts of him would have taken a sinister turn had he demanded, say, a shot at an assistant coaching position or entree into Rice classrooms to earn a degree.

A gag incident gives us a glimpse into the culture of the time, and what would have happened if Shelton spoke up for himself. In 1928, on the floor of a Rice pre-law club meeting banquet, a fake document was read. It purported to be a Faculty-Administration appeal “in the name of Equality” for support of a new policy of accepting “Negro applications.”

The reading drew gasps.

As the student newspaper recounts, most of the Southern-born Rice students shouted “Down with the black Apes…. Negroes at Rice? Hell, no! I’ll be damned if I’ll go to school with a Negro — even if they are clean!” Then, this:

When one “Northerner” argued that integration was a “normal thing to do in this free land of equality,” the room became a “seething mass of perspiring faces and wild tempers.” Those who defended integration were almost “hooted out of their seats” and a 3-1 majority in favor of segregation was recorded before the scheme was revealed as a fraud.

In 1932, the college’s first club to study “racial hatred” was founded. Integration wasn’t mentioned. The goal, instead, was to “look every question squarely in the face and recognize its merits after careful consideration.” This was a form of interracialism, a social movement advocating dialogue between blacks and whites toward understanding of racial and cultural differences. It promoted a kind of halfway step between the Jim Crow status quo and demanding civil rights legislation.

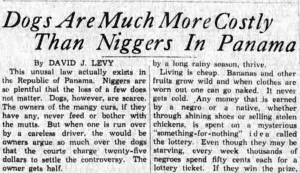

Many social progressives throughout the South supported the movement in cities and college campuses. Those progressives, apparently, weren’t on The Rice Thresher, the student paper, in March 1935.

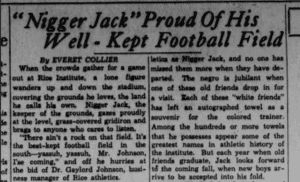

That’s when the below published:

In the following issues, not a single person complained, according to Griffin Smith,* editor of the Thresher in 1963. Attitudes and exceptions were changing in the 1940s, enough for Smith to find a 1943 incident of one black visitor to Rice University which illuminates the difficulty of forming a true two-way street between the likes of Jack Shelton and Riley Johns and the whites they served: “We know you,” the visitor told whites, “because you don’t care what we think of you and don’t try to conceal your thoughts from us. But you don’t know us because we Negroes have to conceal our feelings.”

The prospect of integration at major colleges in South hit near home in 1946 when African-American Heman Sweat applied for admission to the University of Texas School of Law. After he was denied, he sued the UT presidents and other officials in district court. The case ultimately landed in the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in Sweat’s favor and set a precedent for the wide-sweeping Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1953.

In 1947, in the middle of all this litigation, Rice students wrote letters to the Thresher editor supporting opposition to racial discrimination in any form. One suggested since no black college in Texas had graduate facilities for scientific study “why should not Negroes be admitted here?”

By 1948, the Thresher was advocating, against strong criticism, a policy that “all students to the Institute should be judged equally and solely upon scholastic qualifications and capability.” These views triggered searing debate on campus. There were attempts to impeach Brady Tyson, the ’48 editor of the Thresher, according to Smith.

Despite this late 1940s push for acceptance, Rice’s first black graduate student Raymond Johnson would not enroll until 15 years later.

*Small world. Griffin Smith was my executive editor at the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette when I was a reporter there a decade ago. He’s an immensely intelligent and well-traveled man who found my Latin teaching background interesting. He helped me secure my first reporting position despite a lack of formal journalism training (I cut my teeth as a new clerk). He always made time for me. I enjoyed talking to him about about race relations at LR Central, in South Africa and the intersection of telling good stories and chronicling public history.