ROBERT TURBEVILLE — It’s been about 50 years since Dennis Biddle tried to dodge the bull rush of Willie Davis, but Biddle hasn’t forgotten what Davis would do after each big hit — he sang the hits.

Somewhere around six times on a fall night in 1951, Davis sacked Biddle, then the quarterback for Columbia County Negro High School in Magnolia. Each time the Texarkana Booker T. Washington High School lineman took Biddle to the ground, Davis would stand over the quarterback, smile and sing, sometimes voicing lyrics about having “mercy.”

“Willie was just overpowering,” said Biddle, who laughed when recalling the game. “I couldn’t even go back to pass. He was all over me.”

Biddle doesn’t remember Davis as a mean guy, even though Davis made his night miserable and helped the Washington Lions to a 55-0 victory over the Owls.

“He [Davis] was a nice guy. He really was nice,” said Biddle, who went on to play baseball in the Negro leagues. “He was just eager to get going, as I can remember… You could tell he would be a great football player. He had the size.”

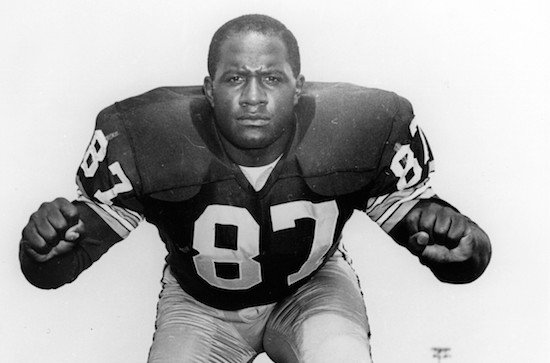

After playing for legendary Coach Eddie Robinson at Grambling State, Davis followed with a 12-year career in the NFL that resulted in his induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio. As a 6-3, 245-pound defensive end, Davis played in five consecutive Pro Bowls and 162 consecutive games and was part of five NFL championships for Vince Lombardi’s dominant Green Bay Packers teams of the 1960s.

Davis, 67, is a millionaire California businessman, the owner of five radio stations across the country and a member of the board of directors for 12 large corporations, including the Packers, Dow Chemical, Kmart and MGM Grand Inc. He’s also a trustee at the University of Chicago, where he received a master’s degree in business administration, and Marquette University.

A self-described emotional player, Davis doesn’t recall the specifics or remember singing in that game against Biddle and Columbia County in 1951: “It was just probably my moment to enjoy the song,” he said with a laugh. But Davis is eager to credit the experiences he gained while playing at a black high school in Arkansas for the success he found afterward on and off the football field.

He even concluded an April 2002 interview with a plea for Arkansas high school students to play sports.

“One thing I would say is playing athletics in Arkansas was where it all started for me,” Davis said. “It turned out be a great experience…. Nothing quite compares to enjoying some athletic success. I feel very blessed.”

This excerpt is from the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette’s Untold Stories, a series of feature articles from 2002 which provide the state’s only detailed resource on its black sports history. Unfortunately this anthology, which preserves a vital part of our state’s heritage, is out of print. I’m organizing a petition to change this. Click here for more info.

A LONG ROAD FROM TEXARKANA

Davis never missed a game because of an injury while playing 2 years in high school, 4 years in college and 12 years in the NFL for the Cleveland Browns and the Packers. But he almost missed his second game, and all the games that would follow, because of his mother, Nodie Bell Davis.

“Yeah, I had played my first game in high school before my mother actually knew I was involved with the football team,” Davis said with a laugh.

Davis’ junior season was his first to play organized football, and his team was scheduled to go out of town for its second game. That’s when Davis had to tell his coach, Nathan “Tricky” Jones, that his mother didn’t allow him to play football.

Jones went to Davis’ home before leaving town for the game to convince Davis’ mother to let him play. It didn’t work. Nodie Bell Davis was convinced her oldest son would get hurt.

“There was an individual a year ahead of me who had been injured during my sophomore year,” Davis said. “His name was Carson Amos, and he never had the use of his right arm again. Every parent and every guardian was kind of concerned about their sons playing football.”

When his coach finally gave up trying to convince Davis’ mother to let him play, Jones left for the school. That’s when Davis gave his mother an ultimatum.

“I just kind of fell apart,” Davis said. “That was the first time I ever did something I felt ashamed about. I threatened to leave home if she didn’t let me play football. At the last minute, she said ‘If you’re going to be that determined, you go and play football Just don’t come to me when you get hurt.’ I remember that almost like it was yesterday.”

He sprinted out of the house soon after gaining her permission and raced about a mile to the school to try to catch the team bus. When he reached campus and turned a corner to head to where the team was to meet, he saw the bus pull away. That’s when he really started hoofing it.

“I saw the bus leave the other way, so I turned and basically tried to cut the bus off,” he said. “I got close enough that somebody looked out the back of the bus and saw me.”

Davis played in that game, and more than 200 games followed.

His mother refused to watch him play until the final game of his senior season, which was the black state championship. Washington, which featured about six players recruited by historically black colleges, won the game to cap an undefeated season.

“Would you know that I was knocked unconscious in that game?” Davis said. “I only remember one other time when I was even close. But by the time I left college and got into the pros, she had become a total convert. You could almost hear her up in the stands.

“At the Hall of Fame induction [in 1981], I was trying to give a speech, and I looked out and saw her. She was crying, and I just lost it. I think I managed to say, ‘Hey, Mom, it’s a long road from Texarkana.’ ”

Four years later, his mother died.

Willie Davis’ Humble beginnings

Life in Texarkana wasn’t easy for Davis, a Lisbon, La., native who was the oldest of three children. His parents split up when he was 8, and he grew up in poverty, working two jobs in high school.

One of those jobs was at the Texarkana Country Club, where his mother was the head cook, and that was about all the exposure Davis had to white America while growing up, he said. He worked in the locker room and helped shine members’ shoes and pick up their towels.

That doesn’t mean Davis totally was tuned in to segregation issues.

“You probably sense that there’s unfairness about some things. You don’t deal with that side of it every day,” Davis said. “Most of my life was lived in a black environment at that time. It’s probably more simple than most folks think.

“I obviously interfaced with white people every day. In fact, it was kind of interesting. These were people that at least treated me with far more dignity than I’m sure I would have been in another situation where there were not as many affluent people. I still left the club and went home to the environment that I was brought up in and most comfortable with.”

Two weeks into his rookie season with the Cleveland Browns, Davis was drafted into the Army, where he played his first game against a white man. Even then, he said it wasn’t that big of a deal “because of how competitive it can be.”

“When I lined up, I wanted to win the battle whether the person was white or black,” Davis said. “There were so many things that influence how you play the game, you don’t get captured in racial terms.”

There was one incident, a game against the host Detroit Lions, when he said he couldn’t help but get caught up in a racial term. Davis would not name the player involved, but he described the incident as “one of the more upsetting moments I had in life.”

“It was pretty clear that I was taking advantage of speed and other things to give him a very tough time,” Davis said, recalling that game against the Lions. “I was down on the ground, and he kicked me in the mouth and called me the big ‘N’ word. It was probably the first time I ever got really upset. I would say that did not help the rest of his day. I not only tried to be competitive, I wanted to do something to him. I remember that because it was almost the only time I felt a sense of the race thing and getting it in my mind-set.”

Want to see the rest of this story? Make sure to sign up for the list below. I’ll send the entire piece and notifications of my new BestOfArkansasSports.com posts – about three a month.